(First appeared in Air India Shubh Yatra, October 2013)

Rome is no beach resort to be experienced sensually with the skin, mind locked up. Rome is intellectually engaging as a city-sized tableau the interplay of politics, religion and art has created. So the monuments exist, some in ruins, as they were in the unaltered, timeless settings of River Tiber and the ‘ear bud’ foliage of Cyprus trees. Rome, like most other historic Italian cities, has resisted the modern temptation to grow vertically. Yet, unlike the city states of Venice and Florence, a Roman holiday is a challenge of distances. After all, it was caput mundi (capital of the world). Rome overwhelms you with its magnificence, and the mega scale on the three physical dimensions – plus the sense of the eternal, on the fourth dimension. Wrapped in a time warp are monuments, distanced by centuries, coexisting contiguously. This delightful puzzle has to be unravelled by joining the dots with the logic of chronology. Then one can decipher the entangled ribbon of human history spanning over 25 centuries.

Rome’s first time capsule is centred around the Palatine hill and the neighbouring ruins of ancient Rome. Here, credible history of its origin gets mixed with the mythology of Romulus, reared by a she wolf. Following the rule of seven Kings came the Roman Republic governed by the Senate from 523 BC. Marking the beginning of the Western world’s earliest civilisation, 25 centuries ago it was a remarkably democratic order that gave way to the Roman Empire in 27 AD. The Emperors lived in Palentine Hill. The palace of Augustus Caesar, restored, is now open to the public. So are the 50 caves under the palace. The adjoining Forum became the centre of public life, processions, victory marches, religious worship and festivals, judiciary and commerce. Today, weeds have invaded the expanse, with only fragments of pillars and arches, shrines, temples and government buildings remaining, but it doesn’t take much to visualise life when Caesar and his entourage passed, making heads turn.

Rome’s first time capsule is centred around the Palatine hill and the neighbouring ruins of ancient Rome. Here, credible history of its origin gets mixed with the mythology of Romulus, reared by a she wolf. Following the rule of seven Kings came the Roman Republic governed by the Senate from 523 BC. Marking the beginning of the Western world’s earliest civilisation, 25 centuries ago it was a remarkably democratic order that gave way to the Roman Empire in 27 AD. The Emperors lived in Palentine Hill. The palace of Augustus Caesar, restored, is now open to the public. So are the 50 caves under the palace. The adjoining Forum became the centre of public life, processions, victory marches, religious worship and festivals, judiciary and commerce. Today, weeds have invaded the expanse, with only fragments of pillars and arches, shrines, temples and government buildings remaining, but it doesn’t take much to visualise life when Caesar and his entourage passed, making heads turn.

Arguably the most impressive architectural marvel of this period is the Pantheon. A pagan temple rebuilt in 128 BC and later converted into a church, it is the oldest standing structure, frighteningly ancient from outside but intact within. At 142 feet diameter, its perfectly hemispheric central dome is the world’s largest prop-less dome. The eternal absoluteness of its geometry has been replicated in subsequent domes including in the Vatican.

Arguably the most impressive architectural marvel of this period is the Pantheon. A pagan temple rebuilt in 128 BC and later converted into a church, it is the oldest standing structure, frighteningly ancient from outside but intact within. At 142 feet diameter, its perfectly hemispheric central dome is the world’s largest prop-less dome. The eternal absoluteness of its geometry has been replicated in subsequent domes including in the Vatican.

At the base of Palantine hill is the site of Circus Maximus. Floods in River Tiber have left no trace of the bowl that could take 150,000 spectators for chariot races.

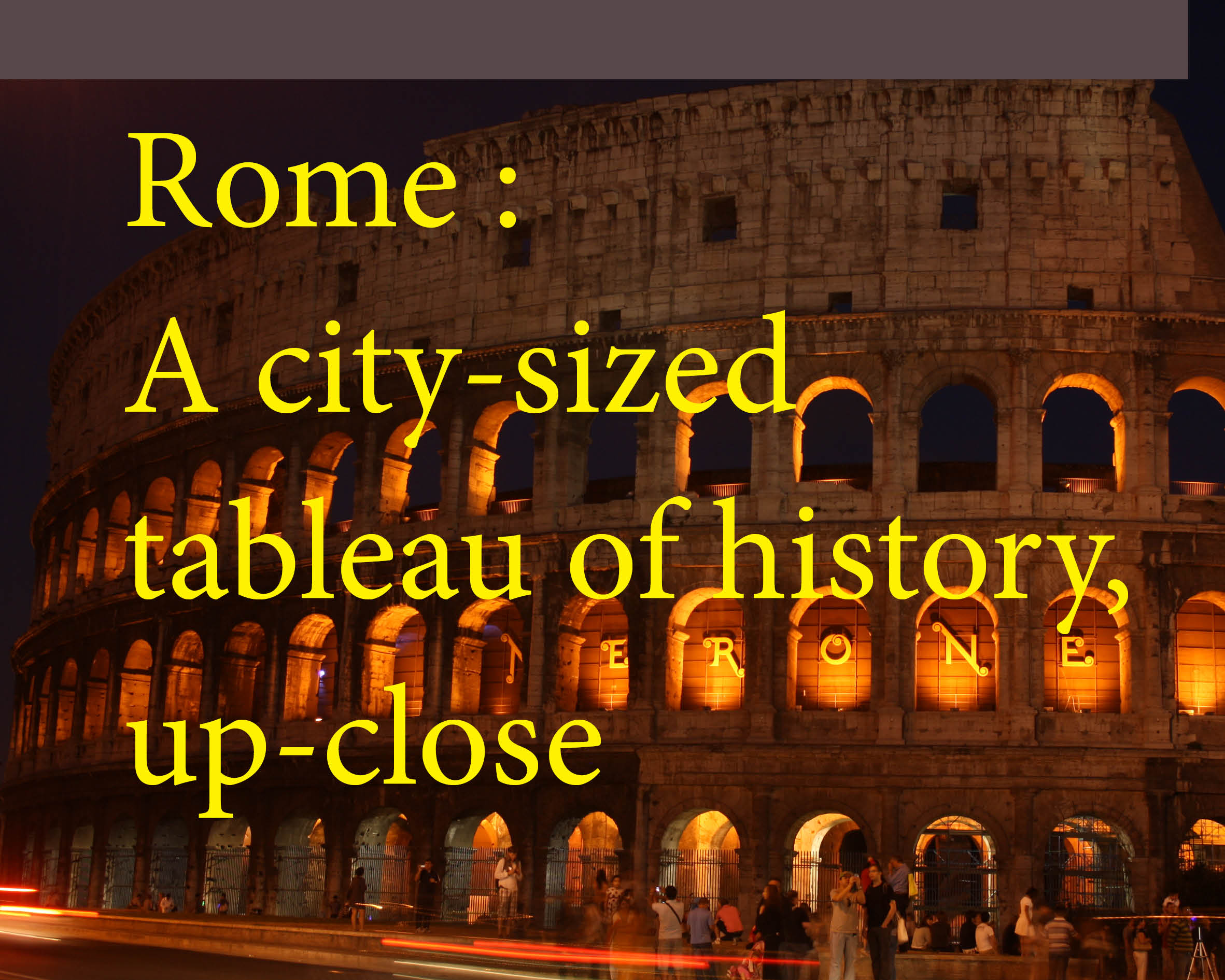

Colloseum, the iconic elliptical amphitheatre, has had better luck. Much of the 72 AD structure is still intact, including the underground cages for wild animals and gladiators, for whom ‘the only exit was death’. It could seat 50,000 (more than the Wankhede Stadium in populous, 21st century Mumbai). Once the centre of blood sport, this 48 meter high structure has now come to symbolise the fight against capital punishment. Its night illumination turns golden whenever a death-row prisoner is spared his life anywhere in the world. On the night of my visit, the Colloseum had that golden glow, celebrating the triumph of life over death somewhere.

Colloseum, the iconic elliptical amphitheatre, has had better luck. Much of the 72 AD structure is still intact, including the underground cages for wild animals and gladiators, for whom ‘the only exit was death’. It could seat 50,000 (more than the Wankhede Stadium in populous, 21st century Mumbai). Once the centre of blood sport, this 48 meter high structure has now come to symbolise the fight against capital punishment. Its night illumination turns golden whenever a death-row prisoner is spared his life anywhere in the world. On the night of my visit, the Colloseum had that golden glow, celebrating the triumph of life over death somewhere.

Pleasing people and the Gods

What prompted the rulers to create such huge theatres of entertainment and worship, in a city whose maximum population was a million, a quarter of them slaves and majority of the rest the poor in wooden houses that were consumed by periodic fires?. The answer to that come to me from an unexpected source : a video game called Caesar. Holding a cardinal lesson for today’s rulers in democracies as well as autocracies, the game is all about how well a player manages to please the Caesar, the Gods and the people. It requires perpetual alertness to constantly develop infrastructure, industry and business, even while catering to people’s need for education, entertainment, not forgetting the Gods who wreck havoc if new temples – bigger, each time – are delayed…

Julius Caesar, before he wrested power, was in charge of the city’s entertainment. He is believed to have done a good job, giving quality entertainment and earning popularity.

Julius Caesar, before he wrested power, was in charge of the city’s entertainment. He is believed to have done a good job, giving quality entertainment and earning popularity.

Fast forwarding past the middle ages, the decline of the Empire and the ascendancy of the Papacy, the next epochal phase in Roman history is Renaissance, also the golden era for Italian art and architecture that featured Michelangelo, Bernini and Borromini among others. The Borghese Gallery, together with the Vatican Museum holds the lion’s share of Italy’s priceless art, the rest being in Uffizi in Florence. The immaculate ceilings of the Borghese Gallery and the unending golden stretch at the Vatican museum ceiling, both incidental to the feast of art objects at eyelevel, exemplify the Italian art- for- art’s- sake attitude afforded by patronage of the State, Papacy and aristocracy. The Borghese Gallery lost 60 works of art to Napoleon after his sister married a Borghese. Even after Napoleon’s defeat, they could not bet be reclaimed because they were ‘sold’. They are now part of the Louvre, Paris.

The professional rivalry between Bernini and Borromini produced some sculptural and architectural marvels. Bernini is the hero of the Borghese Gallery and his David exemplifies the play of power and dynamism in baroque art. The Piazza Navona, the site of two churches and three fountains, is also the site of a Bernini masterpiece, the Fountain of the Four Rivers – the Nile, the Ganges, the Danube and the Rio de la Plata – from four continents. Most guides tell a story: Bernini’s sculpture shows exaggerated revulsion as if displeased with Borromini’s ‘ugly’ church yards away. They will clamp up sheepishly when reminded that the church was built after Bernini finished his wonder in stone. (The piazza and the fountains feature in Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons.)

The professional rivalry between Bernini and Borromini produced some sculptural and architectural marvels. Bernini is the hero of the Borghese Gallery and his David exemplifies the play of power and dynamism in baroque art. The Piazza Navona, the site of two churches and three fountains, is also the site of a Bernini masterpiece, the Fountain of the Four Rivers – the Nile, the Ganges, the Danube and the Rio de la Plata – from four continents. Most guides tell a story: Bernini’s sculpture shows exaggerated revulsion as if displeased with Borromini’s ‘ugly’ church yards away. They will clamp up sheepishly when reminded that the church was built after Bernini finished his wonder in stone. (The piazza and the fountains feature in Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons.)

The Fountain of the Old Boat at the foot of the Spanish Steps is a good excuse for guilt free passivity and people watching. Another neighbouring piece of history from more recent times is Italy’s first Big Mac. Conspicuously missing is the familiar red and yellow in the branding, done purely in functional black – a compromise concession in the face of local opposition to the entry of the American fast food MNC. The protest against the cultural invasion it represented later grew into the ‘Slow movement’.

A coin for a return

The Trevi Fountain, as tall as a four storied building, but just two meters thick, creates far greater impression of depth, thanks to its Baroque architecture. The water originates from ancient aqueducts that testify to Rome’s engineering tradition. Legends vary. According to the most popular one, you turn your back and throw one coin, to return; two, to get married; three, to get married to an Italian. I threw a lone coin. Local papers had reported that thieves and conniving officials had colluded to sweep the pool and collect the coins periodically. Travel advisories recommend caution when visiting Italy. Unless it was my extra precautions, the pickpockets of Rome seem to have been given more credit than is their due. My four encounters with Italian taxi drivers also did not validate the bad name this tribe had earned.

It is said with permissible licence that digging anywhere in Rome, one finds history before water. Excavation for Rome’s third metro rail turned into an archaeological expedition in 2009, stalling the project but yielding many finds. The past buried under Circus Maximus is also being dug out. Who knows what the Eternal City chooses to reveal next from its concealed treasures?

It is said with permissible licence that digging anywhere in Rome, one finds history before water. Excavation for Rome’s third metro rail turned into an archaeological expedition in 2009, stalling the project but yielding many finds. The past buried under Circus Maximus is also being dug out. Who knows what the Eternal City chooses to reveal next from its concealed treasures?

I hope the one Euro coin I invested in the Trevi Foundain yields the promised return to find out that.